Sailing War Zones and Cultural Conflicts [Part 3/3]

Veterinarian Dr Lynn Simpson is a veteran of Australia’s live export trade and a veteran of Red Sea and Persian Gulf voyages delivering sheep and cattle to the Middle East. She speaks to HRAS about her experiences sailing with a mix of cultures on board through regions where their countrymen were at war.

What cultural issues were there with a mix of nationalities on board the livestock carriers you worked on?

It used to be quite tricky sometimes if you had a Muslim crew and we would trade with a country like Israel. There would be Palestinians on board who obviously had a deep-seated problem with stepping on what is considered Israeli soil. I had Palestinian officers who were lovely, they were really rational, they would speak to the Israelis who’d come on board for work, and they would be very professional. But you wouldn’t get them to step off the gangway; no way.

We might be on a voyage where we go to Saudi on the way up the Red Sea and then we go into Israel. So you go from the extreme of Saudi’s Muslim culture to Israel. I was a spectator, but I’d try to calm them down, because they get fired up. Saudi is interesting because it doesn’t seem to have offered much support to the Palestinians, in the Palestinian’s view. They were often angry in Saudi about that, and then we’d get to Israel and they’d be angry about Israel. Once you get them out to sea again, everything was fine.

We’d even been boarded by the Israeli defence force a couple of times. The captain had to stay on the bridge. The chief officer had to stay in the engine control room, an armed guard on each of them, and the rest of us, about 80, were bunched up in the forecastle; three guys with I think M16s pointed at us in the 43 degree heat.

They held us there for a couple of hours, and they taunted us. “Sit down! Stand up! Sit down! Stand up! Sit down! Stand up!” You’re sitting on a scalding hot steel deck. They eventually took us single file into the accommodation and sat us all down on the floor in a room, taking us out one by one to interrogate us – just intimidatory tactics. It not a normal occurrence but, it’s happened more than once. It’s a complete nuisance and welfare risk when you have tens of thousands of animals to care for.

Did you have other encounters with the military?

We were going through the straits of Hormuz one day in 2003, during the second Gulf war, and we had lots of military aircraft and warships around. One time I had a chopper hovering at the side of the ship, watching me kill sheep, only metres away. I still remember the stunned expressions on the pilots’ faces. I don’t know how many they’d watch me kill. I think I had about 20 that I had to dispose of because they were considered diseased with “scabby mouth” and we needed to get rid of them before our first port.

I looked up and saw them, but I couldn’t see any insignias on the chopper, so I didn’t know who they were. I didn’t care. I could see the guns pointing at me, and I just disappeared into the ship.

Working in a war zone is always a depressing and potentially dangerous thing. As a seafarer, you don’t always know where you’re ship’s going to go, you sign up to the ship, you sign up to go wherever it goes.

Sometimes, cultural differences led to victimization on board. What was your experience of this?

Actually, I didn’t realise how quickly my veterinary skills would get sidelined a little bit. I needed to know more about culture, religion and politics to be able to get my job done properly through the day. So, for example, I had to learn all about the Indians essentially giving Bangladesh independence, but from a Bangladeshi point of view, they just gave them swamplands.

Then there’s the cast system, and the Bangladeshis are very submissive to the Indians. One company I worked for had Indian officers and Bangladeshi crew, and at one stage we had a Pakistani captain. The three just didn’t mix, and it was just awful, to the point that I could see very clearly that the Bangladeshis were all tremendously miserable.

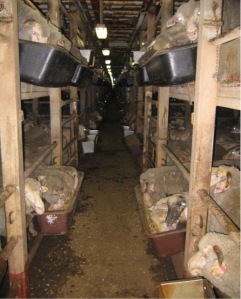

On some voyages, we’d be going through the Persian Gulf in the middle of summer, 55 degrees, humidity in the high 80s, low 90s and this one captain, turned the air-conditioning off in the accommodation. It was an old car carrier, so, it was just one long accommodation space, but he turned the air conditioning off from where the officers’ space stopped and where the crew started.

Not only did the crew have to work down on decks which were stinking hot and full of ammonia gas and CO2 all day, but because the animals generate their own heat there was added heat. The crew would come up for their so-called respite at the end of the day, and there was no air conditioning. Some slept on open decks under the stars, still hot, but sometimes they caught a breeze.

Why did the captain do that?

Because he was a jerk. He was just a complete jerk.

I think the captains are the linchpin to welfare at sea. If you’ve got a good captain who’s got a decent sense of a moral compass, you’ll find the crew are generally looked after and much happier and easier to work with. You get a better outcome for the ship and the company and the animals. If you’ve got a captain that’s for some reason a pain in the neck or a power-tripper, it can be quite difficult.

The captains who caused the greatest difficulty to management and animal welfare were generally relief captains who did not understand how different a livestock carrier is to manage compared to a non-live cargo. The stress levels are through the roof for them, and it was rare that they would return: thankfully.

They were usually so stressed they made life difficult for both the crew and the livestock. If they had the sense to put their pride aside and take advice from others on board, they coped, but were a rare breed, and are to be commended.

The experienced and competent senior officers on a livestock ship are cool under pressure, respect input from people with differing training and expertise and would likely find a “normal” ship boring. I’ve sailed with and learnt so much from some great seafarers.

I’ll always be grateful to them.

How did conflict at home affect crews?

On most of our ships, we didn’t have internet access personally, so communication with home was a difficult thing. Satellite phones are way too expensive for crew to use too often, but when we pass close to land or join the convoy to go into the Suez Canal, there’s a window of connectivity, and everyone’s phones go crazy. Usually news from home brings on a mixture of smiles and melancholy.

One time, there was a lot of Pakistanis on the phone for the whole canal transit, a lot of worried faces, and as we came out of Port Said one of our older crew members went down the gangway and off the ship into a small pilot boat. A few people waved him goodbye. One of the crew members told me: “He’s going home. The Pakistani government has bombed our village.” Most of the crew’s houses had been bombed, 80 percent were either destroyed or wrecked in some form.

The man taken off the ship’s entire family had been killed, and no one had the heart to tell him; they apparently just told him his wife was sick in hospital. Then we had to forget our land lives, or deaths and continue to tend the animals. There is no option to slow down and grieve on a live export ship.

What impact did cultural difference have on shore time?

When crew go into port in different countries, especially westernised countries, if they’re associated somehow with the live export ships, there’s every chance that they’ll be vilified and possibly verbally attacked about animal welfare issues. But the converse side to that is a lot of them don’t get shore leave and if they do, it’s only for an hour or two. So the fact that they’re exploited to the level that they get bugger all short leave protects them from being vilified by people who know what’s happening to animals as a result of the trade, but don’t understand the physical and personal sacrifices these men make everyday of their contracts to provide care for the animals. The crew don’t understand why they are being cursed at, I tell tem when they ask me that people don’t get the real facts, don’t take it personally, ignore them. I know this well, as this happens to me too, even to this day.

I was teaching quite a few of the crew English, just casually on deck every day, in return they would teach me some Pashtun or Arabic. I’d have a few of them come up to me and go, “Oh, doctor, doctor, I have this word. Can you please explain the meaning and how to say it properly?” and they’d just give me a little piece of paper. Each day I’d have a discussion with them, and they wanted to practice their English. It was nice.

At one stage, one of the loveliest captains awkwardly called me to his office, and he says, “Can you please stop teaching them English?” and I’m like, “Yeah, okay. Why?” and he says, “Because we’ve had too many crew jump ship and leave.” I said: “Oh, okay. I didn’t put that into their head. They weren’t asking me, “Where is the train station?” It was an awkward situation and conversation to have because so many of them were jumping ship in Fremantle, Australia. After that, they didn’t get shore leave in Fremantle.

Thank-you Lynn.

AFFECTED BY THIS STORY? Review our Managing Traumatic Stress publication here or go to our publications page to review all our free publications for download. Hard copies can be purchase from The Nautical Institute here.

HUMAN RIGHTS AT SEA HOME PAGE

Important Note. The subject matter and content of all ‘HRAS Interviews’ represents the views of the interviewee only; they do not necessarily represent the views, opinions or charitable objectives of Human Rights at Sea. In the interests of continuing objective, free, fair and open debate on all topics which have a bearing upon, or closely relate to the subject of human rights in the maritime environment, Human Rights at Sea reviews all submissions to the HRAS Interview site and retains sole discretion whether or not to publish the contents. Human Rights at Sea is committed to transparent and free dialogue independent of all political, religious or other perspectives held institutionally, corporately or individually. For further information: enquiries@humanrightsatsea.org.